How the Bear reached the Pacific

Russia's strategic expansion to Asia still pays dividends

Due to entirely foreseeable strikes in the French transport sector, this edition of Geopolis is very late and about a different topic than first intended. Rather than comfortably researching and writing on a high speed train, yours truly was forced to teach himself to drive a stick-shift Renault across Normandy and the Côtes-d'Armor. I stalled, I cried, I somehow got a speeding ticket. C’est la vie.

Isn’t it sad to see the end of a bromance?

“We get a lot of bullshit thrown at us by Putin,” said US President Donald Trump last Tuesday. “He’s very nice to us all the time, but it turns out to be meaningless.”

Breakups do have a clarifying nature to them, however, and Trump seems to be coming around to the idea that caving on Ukraine won’t earn him respect in the Kremlin. Now he’s promising to send more Patriot missile systems, which ought to help Ukraine defend itself from Russian bombardment and strike deeper behind enemy lines.

The world is likely in for a longer, bloodier war than many expected when Trump took office. His campaign claims that he would end the war in just days haven’t panned out, surprising both critics like myself, who expected him to simply abandon Kyiv, and some true believers.

If more fighting is in the cards, Moscow has to find more bodies to send into the maw — ideally not Russian ones. To that end, North Korea is reportedly set to triple its troop deployments, and possibly send its soldiers inside occupied Ukraine itself to fight. Multiple media outlets also reported that Laos will send a military detachment to support Russia’s operations in Ukraine last week, but the Laotian government has denied any such plans.1

For years, Russia has been recruiting guns-for-hire from Central Asia (i.e. the -stans), China, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Thousands of people have taken up the opportunity, but recruits have reported severe conditions, abuse, and withheld salaries.

Not that it matters to Moscow, of course, which hardly treats its own troops any better. A strategic reliance on Asia to help Russia achieve its goals in Europe is a tradition dating back almost to the unification of the state itself, nearly six hundred years ago.

Vast, Frozen and Useful

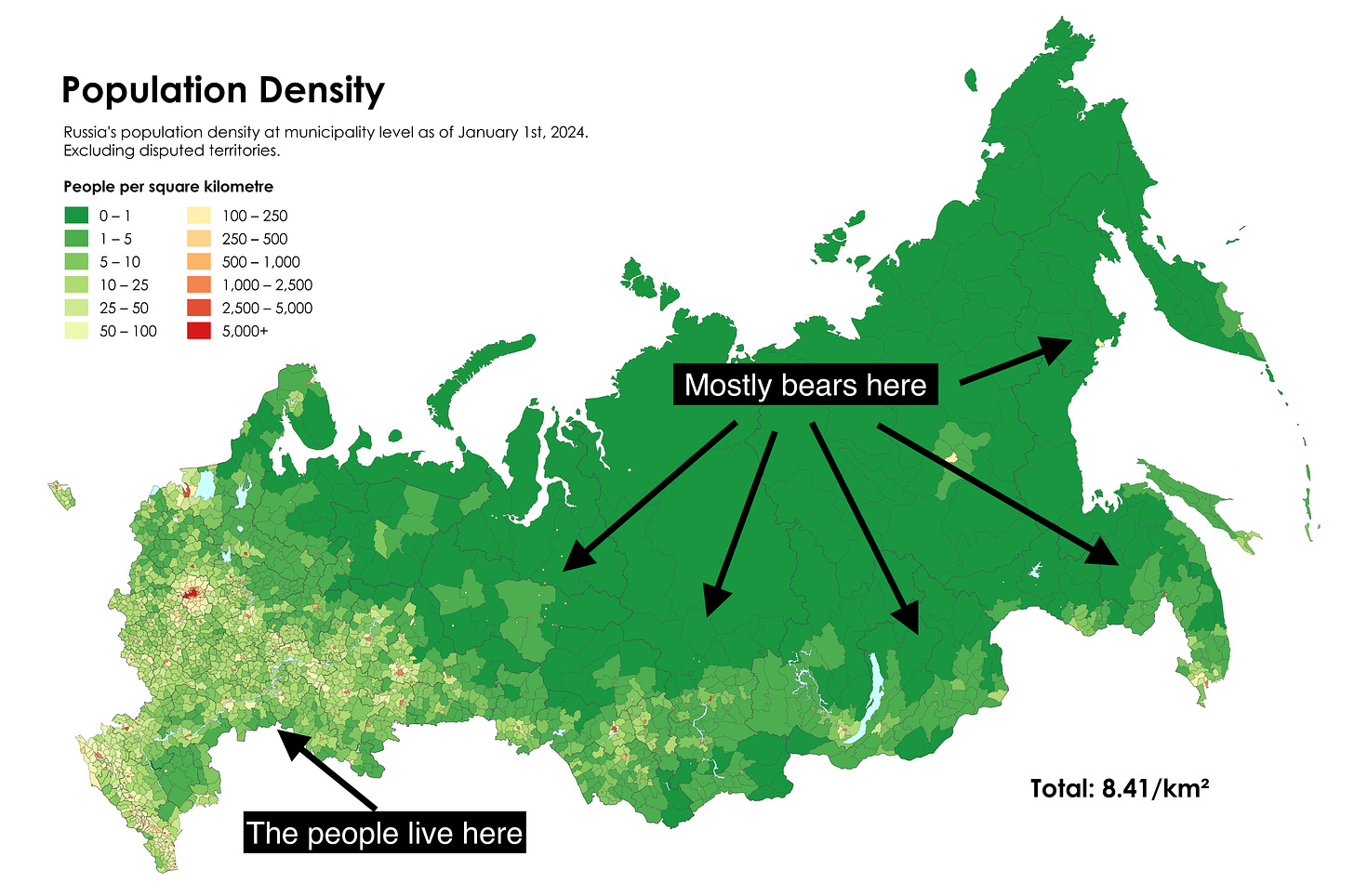

Over three quarters of Russia’s territory is in Asia, but conversely, roughly the same proportion of its population live in its European lands. That’s a feature, not a bug.

Having access to Central and East Asia helps Russia overcome several strategic disadvantages compared to other European powers, most prominently, lack of clear access to the open ocean. While Western Europeans have always been able to use their navies to project power around the world, Russia needs to ask the Turks or Danes to pretty please allow the fleet out.

By stretching territorial control, and eventually a railroad, across the breadth of North Asia, Russia can play power politics in both continents in ways its rivals can’t match.

In the 16th century, just as Europe’s most notorious colonizers were beginning to establish their overseas empires and access the valuable markets of Asia, bands of Russian Cossacks2 were making arduous, violent treks across the Urals. Using gunpowder weapons and fortifications at crucial points, they stretched Moscow’s writ deep into Siberia, and secured lucrative fur tribute, trade routes, and new lands for Russian settlement.

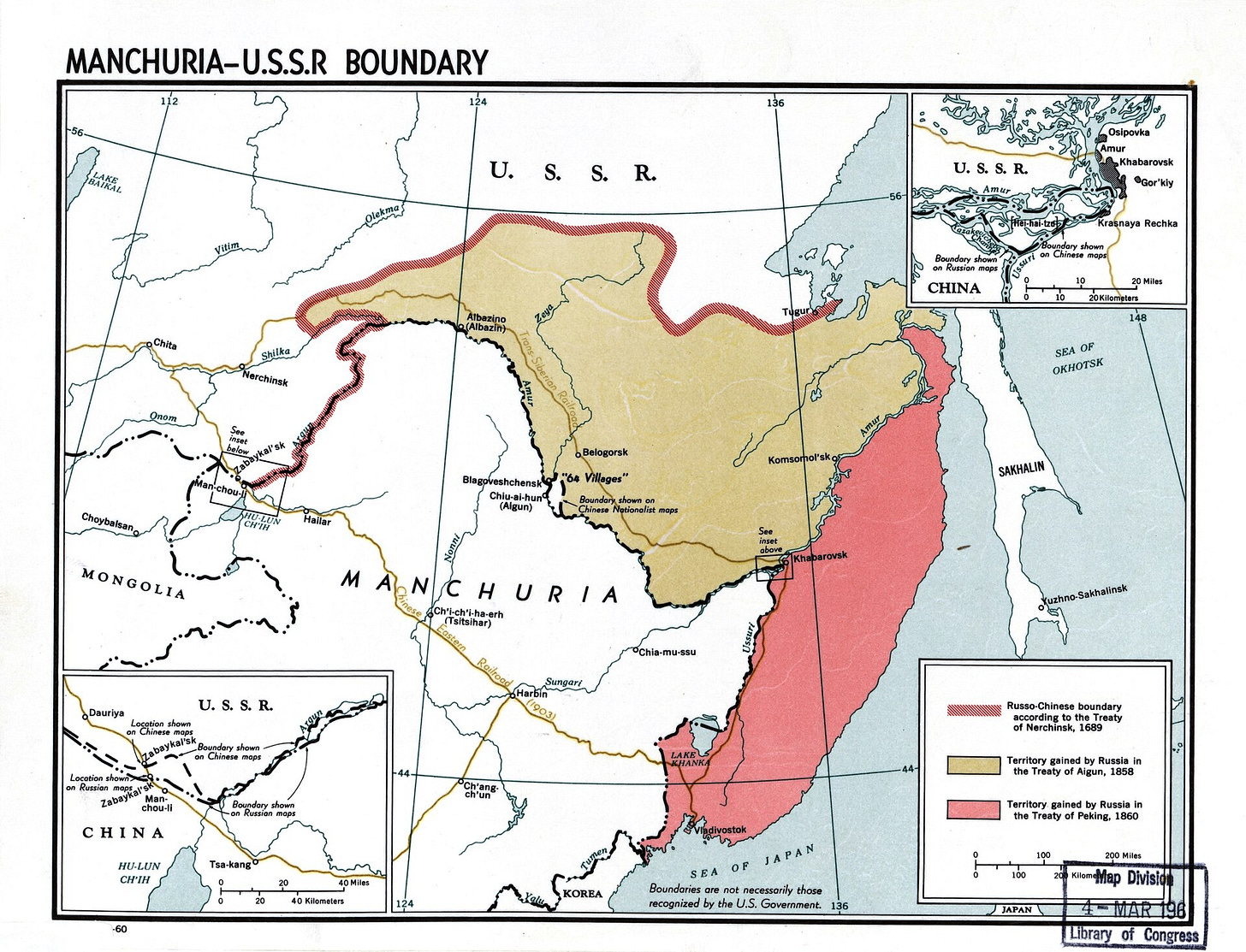

By 1652, Cossacks were skirmishing with Qing Dynasty patrols on what are now the borderlands between Russia and China. The fighting continued off-and-on for decades, before the two sides split the disputed territory along the Amur River in 1689. Moscow’s attention turned to Central Asia, where its troops slowly pushed south across what is now Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan.

Around when Russian troops started pushing up against Afghanistan in the early 19th century, the British began to sweat over the safety of their lucrative colony in India. British and Russian diplomats and adventurers began a series of diplomatic maneuvers across the Himalayas known as the Great Game — but despite anxieties back in Europe, they never came to blows.

The Great Game in Great Qing

Lesser recognized, however, is what my undergraduate advisor Sheila Miyoshi Jager describes in her book “The Other Great Game.” In the late 1850s, Russian official Nikolai Muravev embarked on a renewed campaign of expansion in the Far East, exploiting severe internal upheaval in Qing China. Russia had to act fast, lest their British and French rivals — who recently defeated them in the Crimean War — cut Russia out of the China sphere.

The massive, existentially threatening Taiping Rebellion — probably the deadliest conflict in world history before the 20th century — had broken out in 1850 and seized the vital Lower Yangtze region as the emperor’s armies struggled to resist. Then, in 1856, Britain and France again seized upon Chinese weakness and launched the Second Opium War, putting the Qing Dynasty on the brink.3

All Muravev had to do was station troops along China’s northern frontiers to achieve his goals. The threat of Russian intervention was too great to contemplate, and Beijing conceded a vast swathe of land north of the Amur River in the 1858 Treaty of Aigun, without a single shot fired. Another frontier officer, Nikolai Ignatiev, repeated the feat in the 1860 Treaty of Beijing, expanding the concessions far south along the Ussuri river.

“In one fell swoop, Ignatiev had acquired for Russia a vast domain of about four hundred thousand square miles, roughly the size of France and Germany combined,” writes Jager. “Without the use of force… he had succeeded in extending Russia’s territory to the Pacific and the border of Korea.”

Russia was now a permanent player in the Far East, a role it has never relinquished.

In coming editions, we will return to Korea and how Russia’s rapid expansion to the border radically overturned centuries of foreign policy tradition on the peninsula.

It would be an interesting move from Vientiane, which depends heavily on China for economic exploitation of its massive hydropower potential. It has a tiny population, is very poor, and is bordered by US ally Thailand, and US-friendly Vietnam. Taking a page from Pyongyang in engaging with Russia might open Laotian strategic options… but there’s always the risk that China ices out Vientiane. After all, Beijing has strong relations with other Southeast Asian states, whereas in Northeast Asia it’s Pyongyang or nothing.

Cossacks were wild and hard to explain. Maybe if cowboys in the US Old West formed nomadic pseudo-tribes and occasionally carried out organized violence on behalf of the state, you might have a rough idea. A military historian would probably call them irregular cavalry, but there is a lot more to their culture and history.

This was the war during which British troops burned the Summer Palace in Beijing, one of the great architectural tragedies of world history. Even the ruins are extremely impressive, and worth your time for a visit if you make it to the city.